Is ikigai what we think it is? Letters from Japan #4

have we created a trap for ourselves by misinterpreting ikigai?

Like so many things in Japan, ikigai is both delightfully simple and impossibly complex. In the simple version, the word is a combination of “iki” – to live and “gai” – reason, so ikigai translates to mean finding one’s reason for living. In the complex version, we are all people on many faceted journeys with a thousand colours that enrich our souls, so the idea that there is one perfect intersection of our lives that defines our reason for being seems improbable. There are many interpretations of this philosophy with various origins and various levels of kinship with the original concept.

What exactly is Ikigai?

Ikigai is part of life in Japan. Having a sense of purpose is central to harmonious thought and well-being. In their book Japonisme Erin Niimi Longhurst writes

“After many false starts my jiji (grandfather) finally retired at the age of seventy three. My whole family, a little naively, assumed this meant we would see more of him during the week. For my jiji, though, enjoying his retirement still meant sitting on several boards as a director, giving advice, putting on a suit and having business meetings most days”

This type of example can lead to an idea that discovering ones ikigai is intrinsically tied to our work – an idea that is not lost on many large western corporations eager to extract the highest possible levels of loyalty and productivity from their workers. Looking a little deeper into the origins, I discovered there is more to ikigai than being dedicated to ones job. For the best selling book Ikigai, co-author Hector Garcia travelled to Ogimi in Okinawa, where residents enjoy exceptional longevity. Here’s what Garcia has to say:

“When we asked what their ikigai was, they gave us explicit answers, such as their friends, gardening, and art. Everyone knows what the source of their zest for life is, and is busily engaged in it every day,”

This reads very differently to the first example – ikigai seems to be more about finding what you’re good at and doing it well, becoming a master of your craft, whatever that may be. Being able to earn a living is essential of course, but being bound to the work to such an extent that it reduces the quality of other aspects of life isn’t a prerequisite.

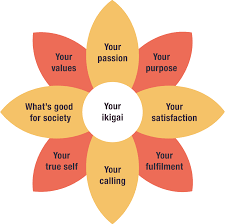

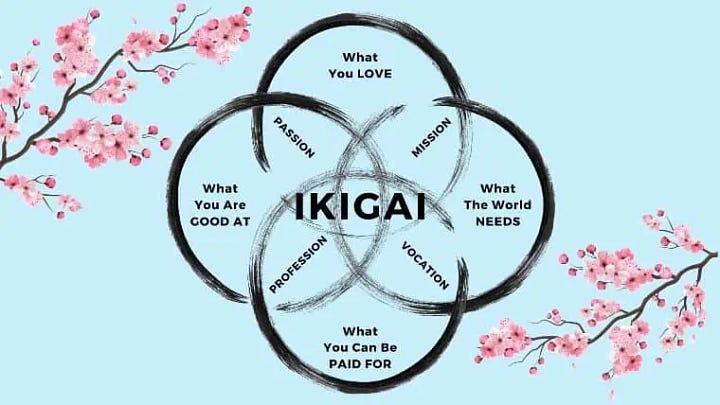

The well known Venn diagram doesn’t sit well with me – it feels too westernized and perhaps too focused on results as a reason for being. A little more research corroborates this idea that the focus on finding a magical intersection is a westernized interpretation (perhaps even a corruption) of the original concept. James Stuber explores the philosophy as expressed by Ken Mogi who describes what he calls the five pillars of ikigai in the The Little Book of Ikigai.

· Start small.

· Release yourself.

· Harmony and sustainability.

· The joy of little things.

· Being in the here and now.

There is no mention of pay, or profession, or mission or any of the elements in the diagram above. That’s not to say the diagram is wrong – but it is perhaps not a true representation of how ikigai works for Japanese people.

Ikigai in my life as a writer

For me the separation between money and life’s purpose is crucial. I’ve never had a well paid job – I’m terrible at networking and entirely inept at the social interaction that goes hand in hand with “getting on”. I’ve never been driven by money or buying things, nor am I competitive, so words like profession and mission send me hurtling back to the horrors of school or being part of a sales team with all the trappings of KPi’s and bonus related performance reviews. It doesn’t seem to fit with the wider concepts of harmony and stability and finding joy in the little things.

Is writing my reason for being?

Would I say my Ikigai is writing? Well it’s the thing I work hardest at, the thing that I keep getting up and trying for. It’s the thing that brings me joy and satisfaction. Other things come close – growing things in my garden, caring for my friends, caring for the wider world and I feel Mogi’s approach gives me the flexibility to enjoy and value all these things, without getting bound up in whether I can be paid for them. Mogi’s approach also means I don’t feel I have to pick one thing and stick to it. Nourishment for my core self can be multifaceted in that joy that is found spent looking at the intricacies of a dandelion is as valuable as the joy of growing a stunning rose, joy found from sitting at the edge of the furnace pools near my home is as valid as the joy I gain from gazing at the ocean overseas.

Ikigai, like so many things seems to be about connecting with our inner self and allowing ourself to truly enjoy what we have, without the trappings of competition that we have been indoctrinated with since we were young. Adopting the idea of Ikigai means I can free my writing from being driven by results - winning competitions, getting a thousand paid subscribers - and be focused on making the work the best it can be with the view that recognition and remuneration are a happy by product. For me, seeking ikigai is a way to focus and calm the noise and ultimately my ikigai – my wild feeling - is to find a sense of connection and meaning that goes beyond the material.

I can’t pretend this video on one of the billboards in Shinjuku is relevant to ikigai but it is so fabulous.

The next letter from Japan will be published on 7th June when we’ll be back on the travel trail, looking at how this idea plays out in real life – we’ll be in Kanazawa and Kyoto and maybe Osaka too. I’d love it if you’d join me!

Until next time

If subscribing’s not for you at the moment, but you enjoy reading what I write (squee!) then a restack, clicking the ❤️ or leaving a comment is a fabulous way to show your support !

A fascinating break down - I love the focus on the little, freeing, joyful things!

A joy of little things passed on to me by my parents, my own little patch, gardening and growing our own food, ingrained like the muck under my finger nails. X