Understanding omotenashi can improve your writing

this Japanese philosophy can be adapted to every aspect of our life with beautiful results

Japan offers so much insightful thinking that choosing to consider the role of Omotenashi in our writing may seem a strange option. How can giving incredible service help with writing? As with so many things, the meaning has roots beyond our initial concept, and these roots inform and enhance our understanding and application.

Dating back to the Heian period (794-1185) Omotenashi is built from two words "Omote" which represents your outward persona and “nashi” which denotes absence or lack. Read together, Omotenashi represents a lack of pretence or artifice, and a desire to wholeheartedly contribute to the happiness of others.

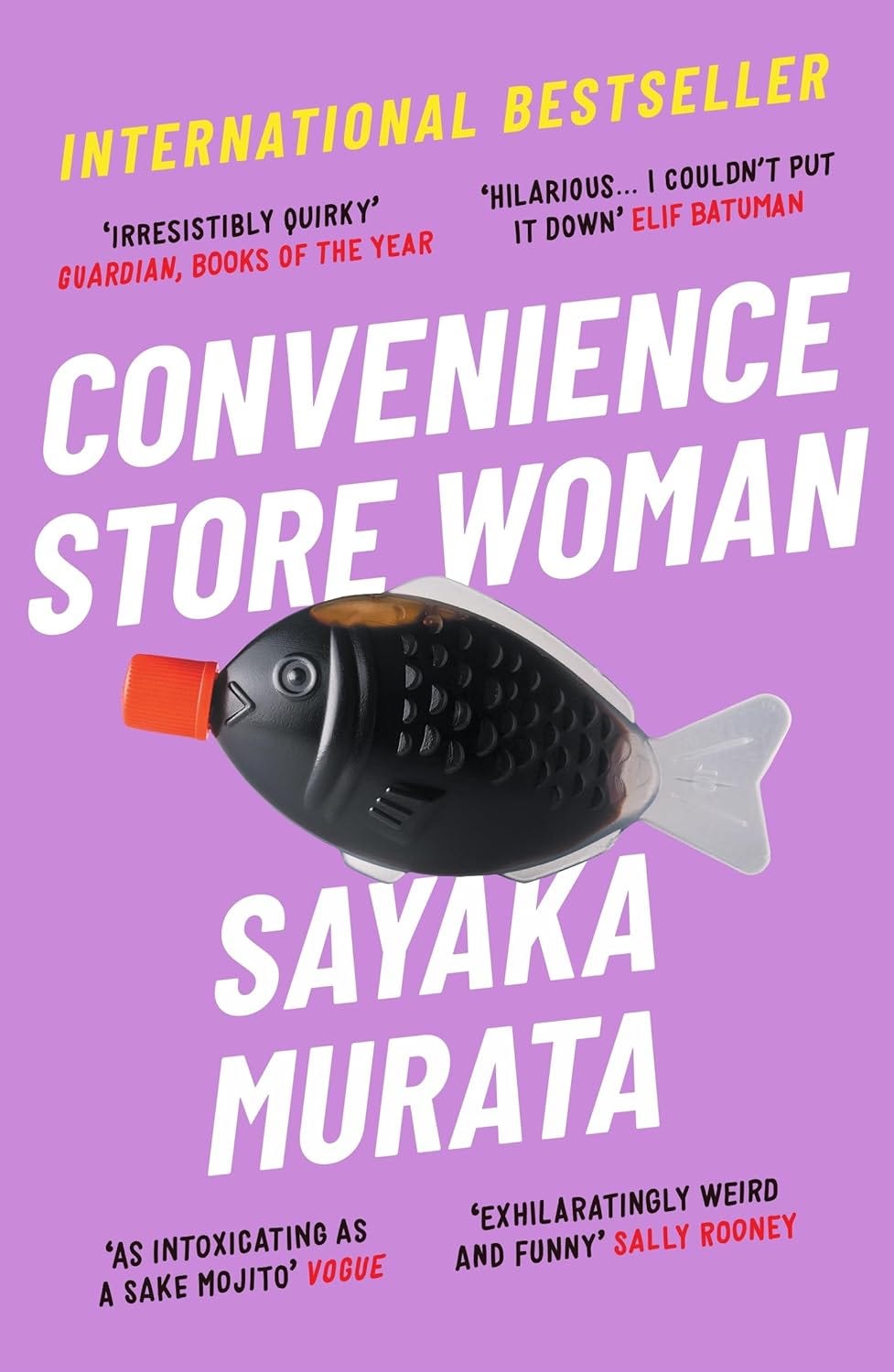

The concept is beautifully demonstrated in Sado, the tea ceremony, where the tea master makes tea in full view, showing their guests the entire process with humility and care. These qualities are present across the Japanese hospitality sector, from the most humble convenience store to the traditional ryokan, and are a central concept of everyday life. It is more than the somewhat performative service found in much western retail and hospitality, it is a core value that demands any service be wholehearted, open, and honest.

Flawless skills are not required (but are a goal, of course). The most important thing in Omotenashi is the pureness of heart behind the action – the desire to serve wholeheartedly.

How does Omotenashi apply to writing?

So how can this apply to writing? One of the key phrases I remember from poetry workshops is “what do you want the reader to take away from this”. In my early writing days, this felt odd. Surely, I just have to write what I want, and the reader will take what they will?

This is true, up to a point. If we look beyond the initial writing stage, which can often be a blur of emotion, and move to the editing stage, considering the reader is essential in helping crystallise our concept. Applying Omotenashi does not mean dilution of our self to please another, it means giving our whole self to please another. As a writer I can hold something back, or I can give my whole spirit to what I’m creating, to what I want the reader to experience.

If I approach my writing like this, the act of editing shifts focus. The process becomes collaborative, between me and my imaginary readers. The loftiness of the writer is diminished – we become firmly aware that are no more valuable than those who read us. When I fully consider my reader I take absolute care to ensure the work I produce is good to read and includes all the cues and clues required to access meaning. This does not mean dumbing down or simplifying, rather it means taking care to fine tune each word, each punctuation mark to ensure that meaning is conveyed and absorbed as wholeheartedly as possible.

How does this work in practice?

To apply Omotenashi to my own writing I bring it at the editing and redrafting stage.

My first step is to consider what I want my reader to take from what I’ve written, be it poetry, prose, or a piece of content for a firm of electrical contractors. My intention must be clear in my mind to allow me to fully edit and revise.

Once I have this clarity, I move on to analysing my own work. I have grown to enjoy this phase - it took some time to let the work breathe enough and become it’s own thing rather than a pure distillation of my emotion. As part of my analysis I ask myself if my work is clear, if my work is beautiful to read and if my work is the result of the best skills and care I have to offer. I consider each punctuation mark, each word, structure and tone. I seek feedback if possible, and consult books if not.

I also have to accept that there is an element that will never be perfect (which is the key tenet of Wabi-Sabi, another valuable way of thinking) but be sure I have done the best I can at that moment. I do not have to be flawless – there is a common concept that no poem is ever really finished. The key to Omotenashi is to seek to serve your reader with honesty and your whole self. This could mean removing a phrase that you absolutely love but introduces ambiguity, it means taking your peers’ advice when they say you need a comma rather than an em-dash (I do love an em-dash). Most of all it means placing yourself in the role or the reader, being sure what you want them to take from your work, and being sure that you’re making it easy and enjoyable to do so.

What do you think?

How does this sit? Do you think there’s a place for Omotenashi in the writer’s world? Do you think considering will enhance or encumber your own writing?

Omotenashi punctuated so many moments of my travel in Japan. We took part in a tea ceremony, which was mesmerising but felt a little detached. For me the most memorable moments of Omotenashi happened in Kanazawa, a small city on the north coast of Honshu. I’ll write about these in my next letter - subscribe to be sure you’ll see it.

Until next time

I’m finding my way a little here in terms of how to build a sustainable newsletter - could you help me understand what you like most, and what you might be happy to pay for? Pop your thoughts in the comments, or complete the poll xx

If you've enjoyed reading This Wild Feeling send me some love! Click the hearts, leave a comment, restack, with a note if you're feeling fancy, or share on your favourite social media ❤️

Very interesting! I'm quite unfamiliar with Japanese culture, so this was an interesting read! Furthermore, applying such a concept to authenticity in writing was clever! Well done!

What a lovely concept! I love editing and think a lot about what the reader will take from it - sometimes I have to pare it back a little too, so they reach their own conclusions rather than trying to force it! This is a lovely way of looking at it.